What is design thinking, and how can it help educators?

At its heart, design thinking is incredibly simple – take a step back from the day to day, and figure out if there is a problem that can be solved, then go solve it. Again, the idea is simple. The actual process, though, is quite a bit more involved than that, and takes some strong communication between parties to pull off. When executed properly, design thinking can take a problem of any size and find actionable solutions to that problem. And there’s almost no limit to what problems can be solved, including problems encountered in the classroom. Teachers are relied on for so much. In addition to educating children, they serve as a caretaker, a role model, a mediator, a motivator and an attentive problem-solver that always has an ear to the ground. With all those responsibilities, it’s clear that teachers need some tools to help tackle it all. Design thinking provides that toolbox, giving teachers a head start on taking down issues they face in the classroom.What does design thinking look like?

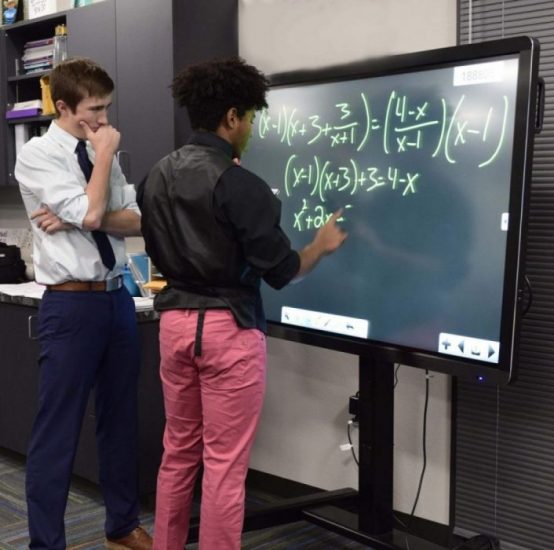

Design thinking is predicated on the idea that spaces and systems should be built around the user’s experience. It’s the user, after all, that must interface with everything in the space, and if maximum productivity is to be achieved – or in this case, maximum learning – then the space needs to reflect that goal in every aspect. In the classroom, the users are both teacher and student, so what can be done in the classroom to get the most out of every lesson? This is the starting point, the main goal. But that’s a bit too open-ended. What does it mean to organize the space around the teacher and student? Ah, now this is where design thinking really begins. It’s best to think of it as a five part process. Those steps include:1. Communicate with users – For teachers, this means approaching other teachers or students, and asking them what they want more of from the classroom. Do they need a fresh way to deliver lessons? Do they need updated technology? Do teachers need an updated curriculum that is easier to implement? Do the students need a classroom that is more comfortable? Do the students want to collaborate more?

2. Define the problem – Getting feedback is the easy part. Interpreting it will take some deeper analysis. It’s best not to lead teachers or students down a particular path, allowing them to fully offer their thoughts without fear of judgment. It’s up to the educator to make sense of these responses, teasing out the actual problem by seeing what things come up again and again. Still, it is important to communicate with as many users as possible, as this will ensure that the problem is properly defined.

Once the problem is in hand, write it out in a sentence or two. If the problem seems too big, break it up into smaller problems that can be worked on over several design thinking sessions. Remember, solving a small problem is better than bouncing off of a large problem.

3. Brainstorm solutions – The problem is clear. Now, it’s time to unleash that creative energy and ideate. Pool together creative resources and bring in other teachers, and even students, to throw some ideas around. The first rule of ideation is – no idea is too silly or too impractical. Write them all down and consider them again and again. Encourage those involved to theorize each idea as far as they can go. Most of this effort isn’t going to lead to a clear solution, but it can help develop additional ideas, and possibly reveal parts of the problem that hadn’t been considered before.

4. Build some prototypes – Now it’s time to turn those ideas into action. One of the beautiful things about design thinking is that it keeps the thinker focused, so when it’s time to execute on an idea, design thinkers know exactly what their goal should be. Without such organized solution building, most people falter when they get to the execution stage.

A prototype means developing the solution to its minimally viable point. In other words, don’t burn a ton of effort building out every single part of the idea and implementing it. If the solution doesn’t work, that’s a lot of time and effort wasted. This can be something as simple as sketching out a new room layout or talking with technology integrators and putting together a possible technology solution.

5. Test the prototype – In the end, it’s the users that determine whether the solution is a workable one. Here, design thinkers have to be flexible and open-minded. The teachers or students are brought in to interface with the prototype, in whatever way they can. If it’s new lesson planning technology, give each teacher some hands-on time with the technology. If it’s new room organization and additional technology to help with student collaboration, give them a simple project to work on.

All the while, be ready to take in feedback, and be ready to hear criticism. It’s rare that a solution is perfect on the first pass, so don’t get too attached to the rough draft. Rough drafts are meant to be tweaked. Hopefully, there will be enough positives to take from the prototype to iterate on the first version.

6. Repeat, if needed – Design thinking is an iterative process, and every iteration brings new insights into the problem, if it doesn’t solve the problem outright. So, as long as educators keep up the design thinking process, they will eventually resolve even the most intimidating issues, even if it is done piecemeal.

The concept of design thinking has been around for more than 50 years. It has shown to be a smart approach for engineers, architects and experts of all stripes. And now, it’s a valuable toolkit for educators as well.